The Dilmun Burial Mounds in Bahrain exceed 10,000 in number and testify to an ancient civilisation that flourished more than 4,000 years ago.

The UNESCO World Heritage List includes over a thousand properties. They have outstanding universal value and are all part of the world’s cultural and natural heritage.

Official facts

- Official title: Dilmun Burial Mounds

- Country: Bahrain

- Date of Inscription: 2005

- Category: Cultural

UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre’s short description of site no. 1542:

The Dilmun Burial Mounds, built between 2200 and 1750 BCE, span over 21 archaeological sites in the western part of the island. Six of these sites are burial mound fields consisting of a few dozen to several thousand tumuli. In all there are about 11,774 burial mounds, originally in the form of cylindrical low towers. The other 15 sites include 17 royal mounds, constructed as two-storey sepulchral towers. The burial mounds are evidence of the Early Dilmun civilization, around the 2nd millennium BCE, during which Bahrain became a trade hub whose prosperity enabled the inhabitants to develop an elaborate burial tradition applicable to the entire population. These tombs illustrate globally unique characteristics, not only in terms of their number, density and scale, but also in terms of details such as burial chambers equipped with alcoves.

About it

That short description demands a wider introduction. Here is an attempt, relying on information from Wikipedia.

Dilmun, also referred to as Telmun, constituted an ancient East Semitic-speaking civilization prominently documented from the 3rd millennium BC onward. Situated within Eastern Arabia, Dilmun’s geographical positioning within the Persian Gulf facilitated its integral role along the trade routes connecting Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley civilization. Notably, it occupied strategic locations in close proximity to the sea and artesian springs, encompassing territories that correspond to modern-day Bahrain, Kuwait, and eastern Saudi Arabia. References to “Dilmun” among the lands subdued by King Sargon II and his descendants most likely refer to this geographical region.

The robust commercial and trade relations between Mesopotamia and Dilmun were pivotal, underscoring Dilmun’s significance in Sumerian cosmology. In Sumerian narratives such as the saga of Enki and Ninhursag, Dilmun is depicted as an idyllic realm existing in a paradisiacal state. For instance predators do not kill, pain and diseases are absent, and people do not get old.

Functioning as a pivotal trading nexus, Dilmun exerted considerable influence over the Persian Gulf trading networks at the zenith of its power. While modern scholarship suggests the Sumerians held Dilmun in high esteem, attributing a sacred status to the region, such assertions lack explicit validation in extant ancient texts. Mesopotamian references to Dilmun predominantly depict it as a trading partner, a source of coveted commodities such as copper, and a vibrant entrepôt.

Furthermore, conjecture exists that the Sumerian narrative concerning the garden paradise of Dilmun may have served as a conceptual precursor to the biblical account of the Garden of Eden.

Well, that final paragraph definitely looks enticing. So how do we go about finding this Garden of Eden, or at least some of these burial mounds?

My visit

The World Heritage Committee continues with a much more detailed explanation of the archaeological site. It gives us a clue.

As mentioned before there are 21 archaeological sites of this kind in the western part of the island of Bahrain. Six of them are large fields of up to several thousand tumuli. The remaining 15 sites consist of 13 single royal mounds and two pairs of royal mounds. They are all embedded in the urban fabric of the A’ali village.

That’s it. The village, or town, of A’ali is easy to reach in a taxi (or perhaps even bus) from Manama. I made it even easier. Instead I simply pinpointed the A’ali Pottery Workshop in my Uber app and was brought to it in twenty minutes from central Manama. From there I walked up and down the main street and into some of the side streets. I managed to discover at least half of the mounds. Sure, I could have done better, if my research had been more thorough. On the other hand, the tumuli do not really differ that much from one another.

A bit more about this heritage site

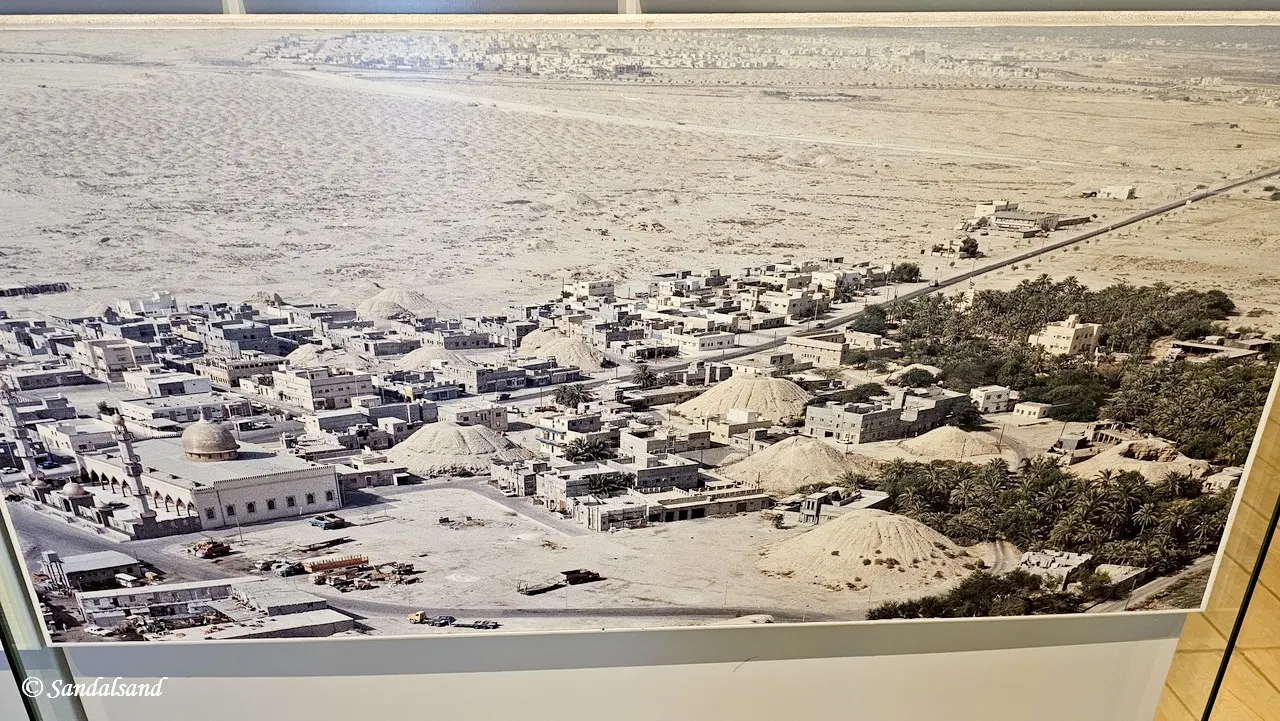

The drive on the highway took me past the larger mound fields to the west and south of the town. The first picture below was shot out of the car window in high speed.

In the National museum the next day it was easy to read more up on the Dilmun civilisation and the burial mounds. There we also find an example of an opened mound, to learn how they used to build burial chambers inside. Have a look at the last two pictures below.

The Persian Gulf countries, which are developing quickly, are always searching for fresh ground on which to expand. The maintenance of Dilmun and other archaeological sites has encountered considerable difficulties. The expansive burial fields are one thing; the large mounds inside the town are quite another. The town mounds have fences surrounding them, as the photos show. Still, they seem to stand out strangely from the surrounding urban settlement and do not at all compare to more famous World Heritage Sites, like the Taj Mahal or the Great Wall of China. I would suppose that this does not increase the importance of the site in the eyes of the locals.

If you are not very interested in archaeological sites, A’ali is still an engaging experience. It brings you out of the modern-day shopping malls of Manama and into everyday village life in Bahrain.

But alas, this was no Garden of Eden.

If you want to read more, have a look at the detailed map and community reviews at the open website called World Heritage Site.