Travel guidebooks on print have a long and proud history, but they are losing popularity, and they meet increased competition. This article is about the evolution of guidebooks in the last 30 years. Do you need them at all, what kind of guidebooks do you need, and what about the bright app future?

Introduction

Why take a 30 years perspective?

I will address this topic by browsing my own bookshelf, PC and smartphone apps. I have been travelling for thirty years and I have an experience with guidebooks equalling that timespan. I’m not stating that my story is typical, nor commendable. It can on the other hand bring forth memories in old-timers and some ideas for new travellers.

What is a guidebook?

A guidebook may be defined as a book of information about a place, designed to be used by visitors or tourists. As part of travel literature the guidebook puts much emphasis on the practical aspects of the visit, like hotel and restaurant reviews, phone numbers, addresses and things to do. A guidebook would normally also include sections on the cultural and historical background of the place.

The guidebook is in its character descriptive and instructive, and one might label it objective and independent as well. Some writers add a personal touch to their writing and possess an ambition to rather be writing other forms of travel literature. The success of these writers in terms of making good guidebooks will be discussed later on.

According to a Guardian article there was a drop in UK and US guidebook sales by 40% from 2005 to 2012. “The best selling international guide from a major publisher sold 21,028 in 2005; 10,201 in 2011.“

Outline of this article

I will be discussing the evolution of the guidebook by first taking a look back in time, to the beginning of the 19th century. I will then explore what a travel guidebook is not. The oral representation of the written guidebook is the tour guide, the narrative and evocative part of travel writing is found in the worlds of travel diaries (blogs) and travelogues. The future is found in digital resources and in printed guidebooks.

The evolution of the guidebook in the long perspective

19th century

Travel guidebooks have a long history but they emerged in the beginning of the 19th century in a modern form. Gideon Minor Davison published in 1822 “The Fashionable Tour: A Guide to Travellers Visiting the Middle and Northern States, and the Provinces of Canada“. Mariana Starke’s “Information and Directions for Travellers on the Continent” from 1824 was even more guidebook-like and offered practical information on travelling on the European continent.

First half of the 20th century

Later, by the turn of the century British John Murray III and German Karl Baedeker had become publishers of very popular travel guidebooks. Baedeker’s guidebooks were issued with a red cover, so Murray created the contrast under the brand of “The Blue Guides“.

Second half of the 20th century

After the Second World War the tourism industry expanded. Travelling became an opportunity for even the rapidly growing middle class in the Western world. The Hungarian Eugene Fodor founded his company in 1949 and produced a series of travel guidebooks in the following years.

Fodor’s became one of the most important publishers in the subsequent decades. Paul Frommer drew on his experience as a soldier in Europe and started in the 1950s his own series of guidebooks aiming at this same customer segment.

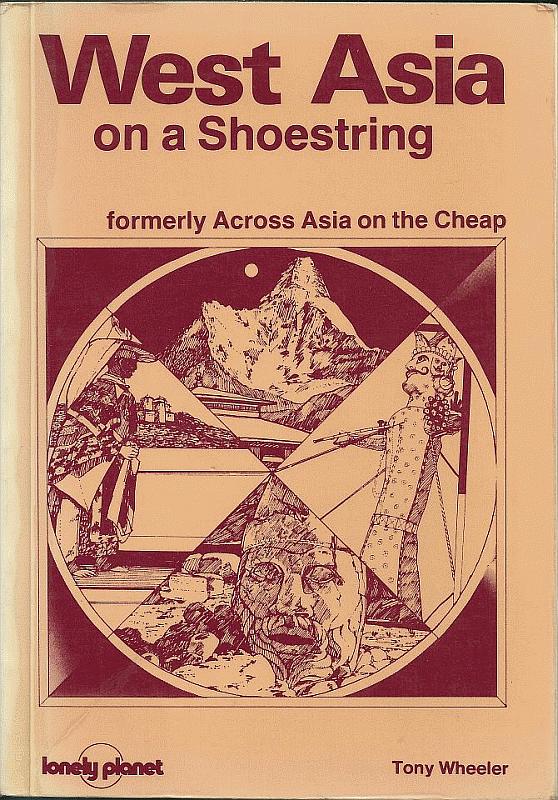

Lonely Planet emerged more or less accidentally in the early 1970’s following the hippie movement. There was a need for practical guides for low-budget travellers, the backpackers. By the turn of the 21st century it was the largest travel guidebook publisher in the world with a wide selection of guides.

But there were more publishers who entered the stage in the last decades of the 20th century. Mark Ellingham created Rough Guides and Hans Hoefer colourized his Insight Guides. In the 1990s Peter Kindersley and Pierre Marchand started DK Eyewitness Guides – among my favourite guidebooks. And then there was Let’s Go, aiming at the American student taking a few months or year off his or her studies.

A travel guidebook is not a tour guide

There have been tour guides speaking on the planet Earth for millennia. They are still here, even a century of so after travellers have been able to read up on whatever the tour guides have got to say. The coming of the guidebook did not eliminate the need for a tour guide.

On the other hand, one may ask this: Do you need a tour guide if you have a guidebook, or vice versa, if you’re on a guided tour why would you need a guidebook?

My hypothesis is that the presence of the one reduces the need for the other. At best they will give an add-on effect, create the basis for a wider perspective, give room for more details, and in short learn more about the subject you study and place you visit. I must admit that my own experience with tour guides is rather limited. Voluntarily or not I have joined tour guides in museums or on occasional daytrips for practical purposes. I’ve even had more or less entire vacations with the presence of tour guides (like this one to Egypt).

Information is key

I have always been struck by how knowledgeable the guides were. More often than not they have also taken a keen interest in showing that off. Guided tours tend to be overloaded in detailed information.

I would find myself more likely to hire the assistance of a tour guide if I was planning an adventure into the heartland of central Africa, than on an island hopping trip to Greece. The latter would have been a personal defeat. There might be some arrogance behind this statement, and certainly a high degree of individuality. On the other hand what is in principle the difference between me and a highly untrained tourist/traveller who would prefer a guide even in that latter case?

I do not believe tour guides are about to disappear any day soon.

A travel guidebook is not a travelogue

In preparing this article I was first tempted to merely link to the eminent article “On Travelogues” by Iain Manley and lay down my pen with the possible exception of commenting on his under-developed paragraphs about travel blogging. I chose to drop the comment and instead present a few contemplations of my own with respect to the theme I am exploring here. Manley refers to an article by Paul Theroux and I would also like to draw your attention to the interesting distinction on Wikipedia in terms of travel literature and also the article on guide books.

Humans have always been interested in hearing about the adventures of travellers in faraway countries. Key names from the history of travel literature include Odysseus, Marco Polo, Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver, and the stories by Jules Verne. We find the same in the history of cinema: James Bond’s travels to all corners of the globe in every film spurn our fascination. Indiana Jones is another example and so is Lawrence of Arabia. Stories like these have reached the wider audience often with a fictitious content, but not always without a factual base.

The fascination

The fascination for the travelogue is also reflected in the world of the more academically and intellectually inclined readers and viewers: “Heart of Darkness” and “Apocalypse Now” is a book and film respectively of that type, and so are the official or unofficial accounts and biographies of known, actual persons.

Our fascination for big personalities throughout history has often been founded on their geographical achievements – they have left home, entered the world of the unknown and been part of something we have not experienced ourselves. Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, Columbus, Magellan or David Livingstone. We Norwegians take great pride in reading about Leiv Eirikson, Roald Amundsen and Thor Heyerdahl.

On the other hand I suppose that Thor Heyerdahl’s travelogue (account) from his Kon Tiki expedition has not resulted in many readers following suit. Henry Morton Stanley’s expedition in the footsteps of Dr Livingstone has probably been reiterated by more, I presume. Certainly the travels of Marco Polo are popular: The Silk Road is one of my own unaccomplished dreams.

A point of view

My point is that these stories, these men (almost all are about men) have intrigued armchair and actual travellers for centuries. The stories were primarily written with an evocative and narrative end. They were meant to entertain, stimulate the readers’ fantasy, generate sponsors and financing for future trips, or simply to brag to the world at large or to the elite group of gentlemen at the Explorer’s Club. (We find modern day parallels in the world of travel bloggers, by the way.)

These travelogues were not meant to be instructive of what to see and do, and where to stay. That need is dealt with in the world of travel guidebooks, although some tips may be abstracted from travelogues as well.

My travel guidebooks in the analogue world

My consumption of guidebooks has followed two lines, the analogue and the digital. Naturally this has a corresponding time line as well, the first before the latter.

The analogue line is about printed media in the shape of a book. For me there has been a clear development from guidebooks heavy on text and details to guidebooks relying on pictures and other forms of illustrations.

Examples of the first kind, the textbook, are Lonely Planet and the South American Handbook. Certainly the latter, but also many of my Lonely Planet guidebooks are as thick as the Holy Bible. They are (were) by their readers treated as bibles too. In the case of the South American Handbook it was even printed on “biblical” paper, i.e. very thin paper and almost verse-like in its descriptions.

For my part, these thick volumes were helpful in my earlier years, on long-term travels, on non-settled itineraries. When I was using the 1987 edition of the SA Handbook it had been around for decades already, and it had set the standards for all other travel guidebooks aimed at backpackers and budget travellers. Lonely Planet was in my early years little refined and even hastily prepared – like the one I used on my Middle East trip of 1986.

My recent years

I have hardly used that kind of guidebooks since the early nineties. I have in recent years instead found Lonely Planet’s books too clumsy to use on the street, and too detailed about places I’m not going to.

In the last 15 years or so I have gradually been shifting over to easier guides. By this I mean travel guidebooks focusing on a particular city (like Barcelona) or region (like Provence). Many of these guidebooks (like DK Eyewitness Guides) are much more illustrated, often with 3D-like maps and pictures of palaces and city centres. They are made for travellers in the modern consumerist society: Be inspired, point to the place and pay the ticket, consume and digest.

This has to do with my vacations: I have known where to go, roughly what to see, and (travelling with children) roughly where to stay. I now like to get inspired about where to go in the region I’m visiting, get my bearings right in a city centre with a good map and receive a hint or two to what areas to avoid when hunting down a place to eat. (I don’t like being told which restaurant to eat at, only to find umpteen LP readers filling up the tables.)

My guidebooks in the digital world

The second line of development in my world of travel guidebooks is the digital line. I have like so many others moved in the direction of using internet resources. There are two trails here.

Home-printed stuff

One of them is the mix between paper and net in which I have collected an assorted range of links and text from various sources on the internet and aggregated that content into one singular file. That file is printed.

I have been using this in a number of cases in the last 5-10 years. For my Andalusia 2012 trip I made a comprehensive plan based on numerous sources and made it available on my smartphone and on hardcopy. We brought along a couple of guidebooks as well, but the plan was produced without the help of a traditional guidebook.

My self-made travel guidebooks are limited to what I really need. Some publishing companies like Lonely Planet offer on-demand printing of pdf-documents, with content from their websites. This may be cheaper but does in no way offer the real benefits of the digital world. Instead it looks strange to see tourists on street corners browsing their 60 stitched pages of self-made pdf-guides trying to find their whereabouts. With so many pages I would say that even a 300-page paperback guidebook offers a handier alternative.

The use of apps

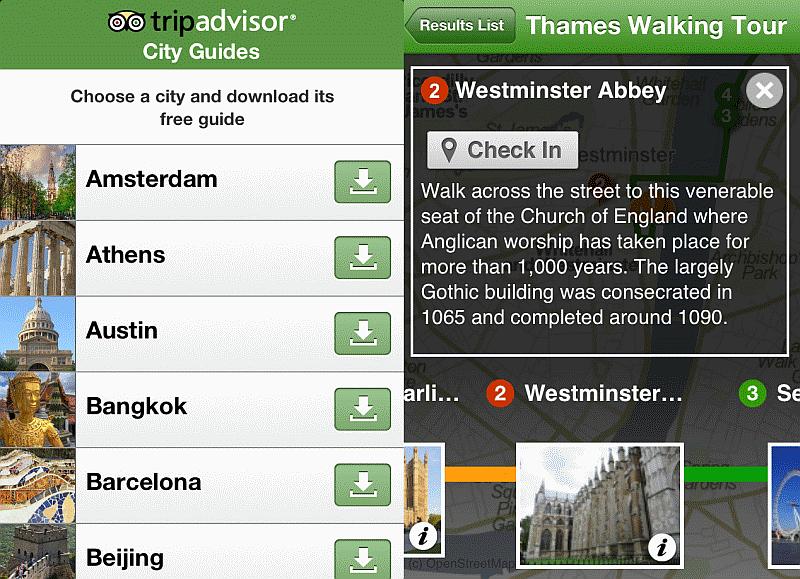

The other kind of digital resource is online or offline copies (apps) on a PC or smartphone. As is often the case with important technology shifts, these guidebooks are frequently not from the traditional paper pushers. They have been issued by the new breed: Tripadvisor, Wikitravel etc.

This means

This means that I view a guidebook on a screen as equal to a guidebook on printed paper.

Some of the technical solutions have localisation support where you are guided in voice, map, pictures and text on walking tours in a big city. Using all aspects of new multimedia (“augmented reality“) technology we are looking at a bright future. We are not there quite yet.

I used this to a not very successful extent in London in 2012. Walking the streets of London with a “tiny” iPhone in my hand made virtually no sense. And an iPad would have been awkward. In addition the handful of 4-5 different apps had no online connection and the offline versions were not good enough.

In the old town of Tangier later that same year an offline app on my iPhone was everything I had because I had forgotten my printed pdf-guide. On the other hand it is the kind of place where it would have been downright stupid to hold out your iPhone in front of you. “Pickpocketing” would have become reinvented.

Do guidebooks have a future?

“Lonely Planet and Rough Guide has been replaced by Wikipedia and various travel pages on the internet, and by link collections mailed between travelling companions before departure” proclaimed Norwegian newspaper Dagbladet in 2012. They continued to assert that the big advantage of net based travel resources is the interaction between users. Updates are frequent, information is never outdated, and the more practical information the guide includes, the more app-friendly it is.

These arguments are widespread, and they are partially true. A printed version of a guidebook is usually outdated the day it enters the bookshelves. This is not new; it has in fact always been like that.

The difference today is that the printed guidebook has fiercer competition than ever before. The brave new world of internet resources, apps and so on is obvious. The printed guidebook is however exposed to competition from other sources as well. For instance, many cookbooks and coffee table books are entering this segment, primarily aimed at stimulating travelling. This does not mean that the guidebook as such is less important or less in use. It is rather expanding onto a new platform.

The lines of defence

The lines of defence for the printed (analogue) as well as the digital guidebook are:

The attractions of a place do not change every year. My point of view is that a guidebook should share information of a lasting character. You don’t want to miss out on the examples of Bauhaus architecture when you visit Weimar, Germany. That is what I did, as described in this blog entry. (They are a World Heritage Site.) The reader should remember that a recommended secluded beach is no longer very secluded after it has been mentioned in a guidebook.

A guidebook should state roughly the area you are most likely to find cheap accommodation. In many large cities cheap accommodation and good restaurants are located in defined areas. The reader should however be aware that management changes and places get run down.

A good guidebook offers reasonably objective background information on the history, customs, culture, and politics of a place. You’re unlikely to learn all that in your backpacker hostel in Cuzco. The do’s and don’ts of a country do not change every day. Don’t sit on the back seat of a bus in Buddhist countries and do not receive a gift with your left hand in Egypt.

Towards a conclusion

These three arguments are valid in both the analogue and digital world. It does not really matter whether you have a digital guidebook or a printed one. What matters is that you have it.

In my view leaving on a journey to a place you haven’t been and will never return to is downright stupid without a guidebook of some kind. (Perhaps I should label it “idiotic” in the original Greek sense for the word.) You may follow what you heard through the grapevine, i.e. Facebook, and amuse yourself with river tubing in Vang Vieng, but you will not experience anything really. You will not discover what you missed before you have left and it’s all too late. The guidebook offers you the opportunity to read up on things and make a decision on where to go and what to say on an informed basis.

It all boils down to this: When you land for the first time in Cairo you will find yourself completely lost two centimetres outside the arrival hall without a proper guidebook.

Read more

In addition to the sources linked in the text I have found these articles interesting:

Twilight of the Travel Guidebook?; David Page on Matador.

Travel guidebooks: what is the future?; Stephen Mesquita in the Guardian.

PDF Future of Travel Guidebooks; Wade Shepard on VagabondJourney.

Bowker Study Explores Information Habits of Travelers; press release by Bowker.

The future of Lonely Planet & Rough Guides; a chat link on Travelfish.org.

Ditch the guide. article by travel blogger Hank Leukart offering interesting perspectives on the disadvantages of using a tour guide.

I can’t resist this: Have a look at my picture from 1991. Then read the description of it in this guidebook from 1824.

Update

After publishing this (in 2012) I came across a couple other articles worth reading:

How to use a guidebook; Robert Reid serves us a series of compelling argument for using guidebooks.

Real life: Guidebooks. (No longer available online.) In this article on the National Geographic Traveller, Donald Strachan offers insights into the dawn of travel apps.