The Stećci tombstones are a medieval heritage shared by four Balkan countries, uniting art, faith, and history in unique stone carvings.

The UNESCO World Heritage List includes over a thousand properties. They have outstanding universal value and are all part of the world’s cultural and natural heritage.

Official facts

- Official title: Stećci Medieval Tombstones Graveyards

- Countries: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia

- Date of Inscription: 2016

- Category: Cultural

UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre’s short description of site no. 1504:

This serial property combines 28 sites, located in Bosnia and Herzegovina, western Serbia, western Montenegro and central and southern Croatia, representing these cemeteries and regionally distinctive medieval tombstones, or stećci. The cemeteries, which date from the 12th to 16th centuries CE, are laid out in rows, as was the common custom in Europe from the Middle Ages. The stećci are mostly carved from limestone. They feature a wide range of decorative motifs and inscriptions that represent iconographic continuities within medieval Europe as well as locally distinctive traditions.

UNESCO Listing – Background and Significance

Geographical scope

The Stećci Medieval Tombstones Graveyards form one of the most distinctive cultural landscapes of Southeastern Europe. Inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2016, the property consists of 28 selected sites spread across Bosnia and Herzegovina (20), Croatia (2), Montenegro (3), and Serbia (3). These monumental limestone tombstones, known as stećci, date from the late Middle Ages, roughly between the 12th and 16th centuries. They are remarkable both for their sheer number—over 70,000 are known—and for the variety of their forms, engravings, and symbolic decorations.

The stećci are typically carved from local limestone and found in organised graveyards, often in rural or mountain areas. Many bear elaborate reliefs of crosses, crescents, animals, hunting scenes, and abstract motifs, reflecting a unique blend of Christian, pagan, and local traditions. Their wide geographical spread testifies to the cultural and artistic interaction of communities in the medieval Balkans.

UNESCO highlights the stećci not only as funerary monuments but also as enduring expressions of a shared heritage across present-day national borders. They represent social, spiritual, and artistic practices of medieval Europe in this region, bridging communities that were historically Catholic, Orthodox, and in some cases linked to the Bosnian Church.

Origins and dating

The tradition of carving stećci developed during the 12th century, and flourished in the 14th and 15th centuries. It gradually faded with the Ottoman expansion in the Balkans. They reflect a period of political fragmentation and cultural interaction in the medieval Balkans. Local communities created distinct funerary practices. Unlike classical stone sarcophagi or churchyard burials seen elsewhere in Europe, stećci were an indigenous form. They developed independently and left a lasting material record.

The stećci vary in shape and size, including slabs, chests, and tall gabled forms resembling miniature houses. Decorations were carved in relief or incised, often with highly symbolic motifs. These include crosses and crescents, spirals, rosettes, deer, hunting and dancing scenes, as well as geometric patterns. Some tombstones bear inscriptions in the Bosnian Cyrillic script, providing information about the deceased. Others remain anonymous markers of communal identity.

Cultural context

The stećci are remarkable for their association with diverse religious and cultural traditions. They were used by followers of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches, and in some regions by adherents of the Bosnian Church, a Christian community with distinctive practices. This overlap demonstrates how communities with different beliefs shared similar funerary expressions, making the stećci a rare example of a unifying cultural form in a region often marked by division.

Beyond their function as tombstones, the stećci showcase a unique artistic style. Local stonecutters and masons developed techniques that combined abstract design with narrative imagery. The carvings are both decorative and symbolic, evoking themes of mortality, spirituality, and community values. Their craftsmanship reflects not only technical skill but also a regional artistic identity that influenced later traditions.

Preservation and threats

Over centuries, many stećci have suffered from natural erosion, neglect, or deliberate destruction. Urbanization, agriculture, and looting have further endangered some sites. Conservation efforts, particularly those coordinated since the UNESCO inscription, focus on documentation, protective measures, and awareness campaigns. Preserving these monuments is essential not only for national heritage but also for maintaining a shared European cultural legacy.

The stećci were inscribed on the World Heritage List under cultural criteria (iii) and (vi). Criterion (iii) highlights their testimony to a cultural tradition unique to the medieval Balkans. Criterion (vi) recognises their direct association with significant spiritual and artistic practices. Importantly, the nomination was a joint effort by four countries, underlining the shared responsibility for preserving this cross-border heritage.

Conclusion

The Stećci Medieval Tombstones Graveyards stand as a striking testament to the creativity, spirituality, and shared identity of medieval Balkan communities. Their distinctive shapes and decorations reveal a world where diverse traditions coexisted and interacted. Today, they serve as cultural bridges across national boundaries, reminding us that heritage can unite rather than divide.

By safeguarding the stećci, future generations can continue to explore and appreciate one of Europe’s most evocative expressions of medieval art and belief.

That said, I would like to offer one important impression from the graveyards I visited. UNESCO places a lot of emphasis on the preservation of the tombstones. That is understandable. On the one hand, I don’t really see that there would be a major threat to them in terms of mass tourism. However, as my pictures below document, it is quite evident that nature is taking is toll. Most reliefs are barely visible even today, and they will continue to erode over the decades to come. This is perhaps not possible to avoid. After all, they are made from limestone, a very vulnerable kind of stone.

Spotlight on visited sites

This is a serial property on UNESCO’s list. Few people if any would find it feasible, nor worthwhile, to visit all 28 graveyards. I made it to three of them on a round trip of the Balkans in a rented car, in 2025. In my opinion this qualifies as a good visit to realise what this heritage site is about.

The first location was in the southernmost part of Croatia while the two others were in Montenegro. Here are my impressions, photos, and descriptions on how to get there.

In addition to the links below I would like to draw your attention to a website I greatly appreciate, that of Worldheritagesite.org.

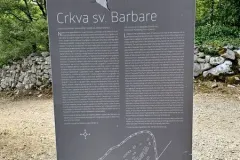

St. Barbara in Croatia

This is one of two stećci locations in Croatia that are included in this serial property. To find it, one will have to drive into the mountains of the Konavle region south of Dubrovnik, near the village of Dubravka. I plotted its location into Google Maps and it worked out really well an the end. However, Google lead me a couple of times into cul-de-sacs and on roads that hardly looked like proper ones.

The cemetery lies up a gravel road of about 300 metres which may not fit all tires. So, you might as well park your car before that. After the cemetery there is a short paved road leading to a hilltop with a large cross. From here there is a great panoramic view of the coast and the hillsides, including the Sokol Fortress.

This particular necropolis has 104 stećak tombstones. Two types of stećci dominate: chests and slabs. Ornaments include motifs of stylised vines, rosettes and crosses, bow and arrow, arm and hand. Read more: One and two.

Grčko groblje in Montenegro

Near the town of Žabljak in the mountainous interior of Montenegro two sites are very easy to reach, if you have your own means of transportation. There is another UNESCO World heritage site in this area, the Durmitor National Park.

On the Grčko groblje cemetery (map) stećci are laid on a slightly elevated, elongated ellipsoidal surface of about 500 m2. There are 49 registered stećci oriented east-west, including: 10 slabs, 27 chests and 12 gabled roof tombstones. Decorations have been observed on 22 tombstones: 12 chests and 10 gabled roof tombstones. The most common decorative motifs are arcades, twisted bands, friezes, frames or edgings with parallel slanting tiny lines, twining vines with spirals or trefoils or only with garlands, palmettes. (Source)

To reach this site from Žabljak drive south and then east on minor roads. At the end of the Fish Lake there is a large road sign and place to park. From here you will find a clear path leading uphill to the cemetery. It is impossible to miss and you will get a wonderful view of the surrounding countryside.

Barama Žugića in Montenegro

The next cemetery on my itinerary is Barama Žugića. It is only 2.2 km from the previous one and even closer to the road (map). These roads are by the way paved although being quite bumpy and narrow.

This cemetery has 300 stećci of which 10 slabs, 50 chests, 10 gabled roof tombstones and 230 amorphous blocks. Stećci of fine workmanship are located in the northern and the central part of the necropolis whereas most of the amorphous ones are located in the southern and south-east parts. All stećci are laid in rows and east-west oriented. (Source)

From this cemetery I continued my drive on small roads into the Tara River Canyon. This is the deepest canyon in Europe and second only to the Grand Canyon worldwide in depth (up to 1,300 metres). I made a stop at the impressive and famous Đurđevića Tara Bridge before returning to Žabljak.

Read more

Find more articles from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, and Serbia on Sandalsand.