Explore the rich history of Almadén (Spain) and Idrija (Slovenia), home to the world’s largest mercury mines, now UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The UNESCO World Heritage List includes over a thousand properties. They have outstanding universal value and are all part of the world’s cultural and natural heritage.

Official facts

- Official title: Heritage of Mercury. Almadén and Idrija

- Country: Slovenia, Spain

- Date of Inscription: 2012

- Category: Cultural

UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre’s short description of site no. 1313:

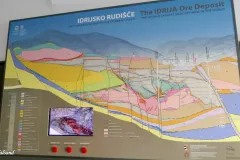

The property includes the mining sites of Almadén (Spain), where mercury (quicksilver) has been extracted since antiquity, and Idrija (Slovenia), where mercury was first found in AD1490. The Spanish property includes buildings relating to its mining history, including Retamar Castle, religious buildings and traditional dwellings. The site in Idrija notably features mercury stores and infrastructure, as well as miners’ living quarters, and a miners’ theatre. The sites bear testimony to the intercontinental trade in mercury which generated important exchanges between Europe and America over the centuries. Together they represent the two largest mercury mines in the world, operational until recent times.

A few words about mercury

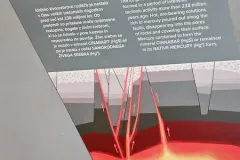

Mercury, also called quicksilver (chemical symbol Hg), is a naturally occurring element known for being the only metal that is liquid at room temperature. It primarily exists in the mineral cinnabar (mercury sulfide). Historically, mercury was used in alchemy, medicine, and as a pigment (vermilion), and played a significant role in gold and silver extraction through amalgamation. It was also used in industrial processes like felt production and in scientific instruments such as thermometers and barometers.

Today, mercury’s use has declined due to its toxicity and environmental impact, but it remains important in fluorescent lighting, some scientific equipment, and small-scale gold mining. Its role in dental amalgams and chemical production is diminishing due to health concerns. Mercury is a persistent pollutant that accumulates in ecosystems, leading to international efforts like the Minamata Convention to phase out its use and mitigate its environmental effects.

My visit

This heritage marks the two largest mercury mines in the world. Their operation lasted for centuries, in Slovenia and Spain. Today they are open for visitors who want to learn about mining and mercury (quicksilver) as a mineral.

A look aside, to Spain

Almadén is located in the Spanish province of Ciudad Real, within the autonomous community of Castile-La Mancha, some 300 km south of Madrid. According to UNESCO mercury mining in Almadén dates back to the antiquity, but took on a much more important position after the discovery of America.

On Wikipedia we may read this: “Beginning in 1558, with the invention of the patio process to extract silver from ore using mercury, mercury became an essential resource in the economy of Spain and its American colonies. They used mercury to extract silver from the lucrative mines in New Spain and Peru. Initially, the Spanish Crown’s mines in Almadén in Southern Spain supplied all the mercury for the colonies…”

Sandalsand has never been to Almadén, but I have visited the town of Idrija in the western part of Slovenia, about an hour drive from Ljubljana.

Idrija, getting there

My visit was a day-trip from Ljubljana in a rented car. The first part of the drive is on swift, straight roads south from Slovenia’s capital. The second part is much more scenic as it involves passing through a mountainous landscape with sharp curves and some open farm land. Idrija is a small town nestled between hills with a couple of rivers crossing through the middle. The architecture and atmosphere is inviting and pleasant.

I made this a three-fold visit, although there are more sights to see if you look around and spend a night. The first part is the town itself, the second is a guided visit into the Anthony’s Shaft Mining Museum, and the third is a visit to the now abandoned smelting plant on the edge of town. What follows is a description of all three elements, with images.

Idrija town

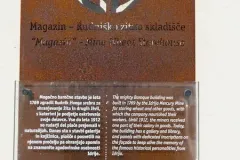

The town enjoys a pleasant location and holds a population of about 6,000. It owns its reputation to the mining industry which is now a thing of the past. Today the authorities have been clever at developing a tourism industry based on its history. A number of plaques around town describe the particulars related to this and that building or square. The city centre is quite small and easy to get around in by foot.

One should pay a visit to the Idrija Municipal Museum housed in the Gewerkenegg Castle, a 16th-century castle built by the mining company. The museum offers a comprehensive overview of Idrija’s mining heritage, the global significance of mercury, and the miners’ daily lives. Exhibits also include the geological formation of mercury deposits and Idrija’s lace-making tradition.

I walked around town but missed the Kamšt Water Wheel, a massive wooden water wheel, built in 1790. It used to power the mine’s pumps to prevent flooding. It is one of the largest preserved water wheels in Europe and a testament to the ingenuity of early industrial engineering. Find the wheel a bit outside the centre of town, for another kind of impression of this Heritage of Mercury.

Anthony’s Shaft Mining Museum

This is the oldest preserved entrance to the Idrija Mercury Mine, dating back to 1500. Visitors can explore the underground tunnels and see how miners worked, including tools, equipment, and a reconstruction of mining techniques. Guided tours bring the mine’s history to life and highlight the challenging conditions miners faced. I joined the hour long tour quite deep into the mine. The tour covers several layers with wooden and stone steps in between. There are a number of tableaux depicting scenes from the mining production. This was really interesting.

Smelting plant and museum

The preserved smelting plant showcases the processes used to extract mercury from ore. Demonstrations and exhibits explain the smelting techniques that made Idrija a leader in mercury production. A new and modern museum describes the use of mercury throughout the centuries, how it was mined and exploited, and also the transportation of the ore from the Idrija mines to foreign markets. There are tours with guides, but also audio guides for individual visits.

Outside Idrija

Also, if you have time to spend, you should venture into the surrounding landscape. The mine’s operations left a mark on the local environment, which is now studied for its historical and ecological significance. Nearby trails and parks allow visitors to explore the area’s natural beauty.

UNESCO has marked four sites in the area in the shape of water barriers, called Klavže. The dams were constructed in the last part of the 18th century to facilitate the transportation of timber to the Idrija mine. The mine or actually mines needed constant supplies of wood. The purposes included the burning of cinnabar ore, construction of supports in tunnels and shafts, and construction of expansive mining structures. Until the early 20th century, rafting on natural waterways remained the preferred method of delivering timber to the mine.

Find more articles from Slovenia (and Spain) on Sandalsand.

Browse to the PREVIOUS or NEXT post in this series.

In the map below, the green colour line shows my road trip into this area. If you zoom in on Idrija you will find the three places in the town that UNESCO has included specifically (Anthony’s Mine, the Smelting Plant, and the Kamšt Water Wheel).